Looking at documentation is quite easy. I can say that I don’t like a certain feature by looking at it, but using that feature is a completely different story. Hence, I wasn’t satisfied with part 1 of this series. Writing a long piece would be annoying, so I decided to take a small snippet from my notes from my quantum mechanics class, I would write down a few of the postulates of quantum mechanics as a benchmark for markdown, TeX (specifically XeLaTeX), and Typst.

I will not be weighing the benchmark based on how quickly I can perform the task, since I am far more familiar with markdown and TeX than with Typst. Rather, the goal is to find out how easily I can figure out how to do something equivalent to markdown and TeX with Typst. I understand that this isn’t the best benchmark in the world, but it’s good enough for my purposes.

Markdown

My normal routine is to work with markdown, since it’s pretty universal, and

pandoc does a good job at making it useful just about everywhere. I’ve heard

some people who are really into Asciidoc say that I should just use Asciidoc,

because it was designed for technical writing and blah blah blah. To be honest,

despite what a lot of people say, markdown is fine. It’s a bit fractured, sure,

but it works—it’s easy to type and easily readable. With a few pandoc

extensions, such as div fences, markdown is actually quite powerful—the same

goes for Hugo, where shortcodes can easily substitute for div fences.

It’s worth noting that I have some extra macros, \bra, \ket, and \comm

defined in my TeX template for pandoc; you’ll see them in the TeX section.

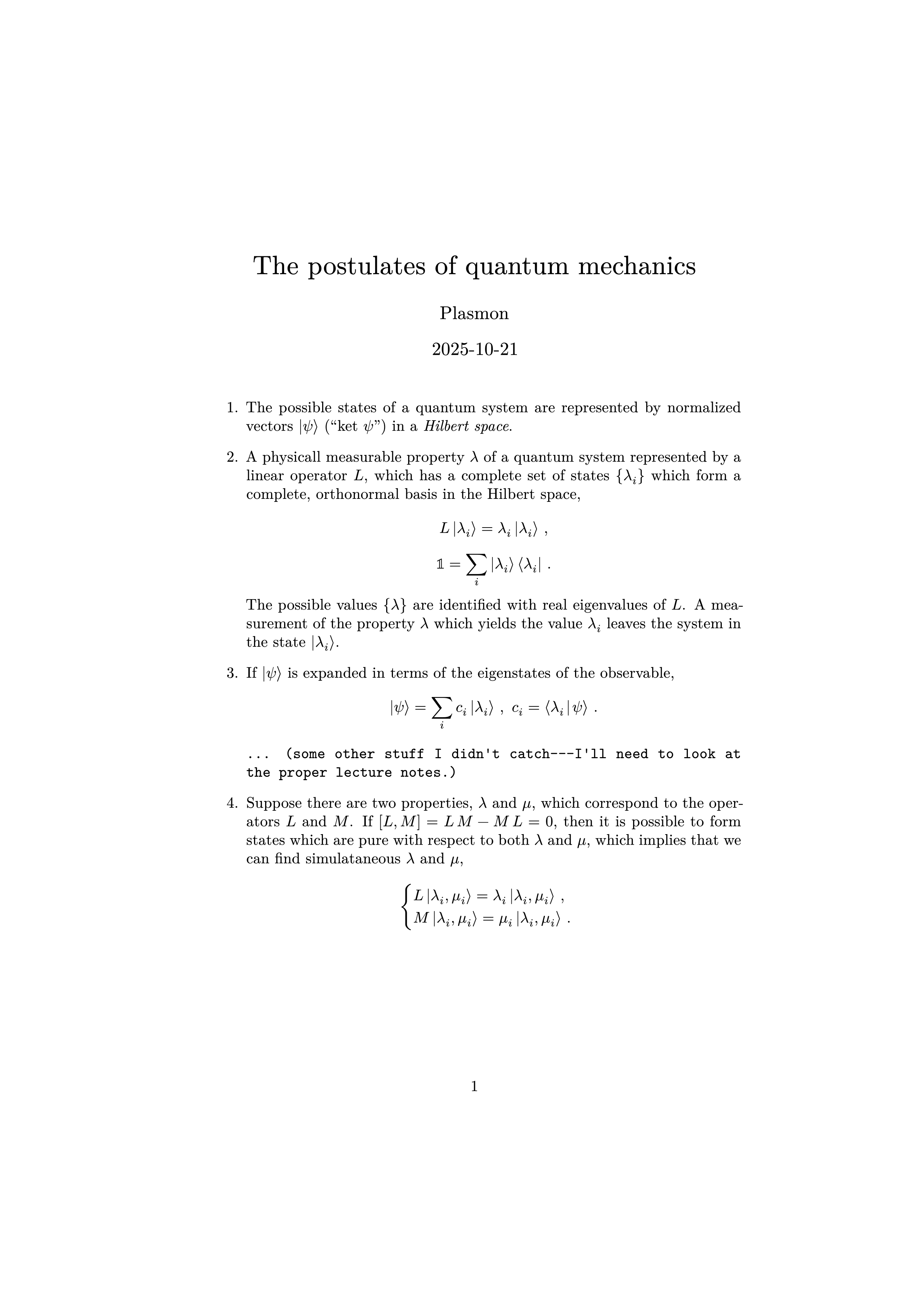

Writing these notes in pandoc was relatively painless, as I’ve used pandoc billions of times by now. I didn’t need to write a super long preamble or anything, so all I needed to do was put in some YAML metadata and get writing. Once I was finished, I compiled the document using pandoc and XeLaTeX, giving me a PDF file.

My original quantum mechanics notes written in Markdown.

---

title: The postulates of quantum mechanics

author: Plasmon

date: 2025-10-21

---

1. The possible states of a quantum system are represented by normalized vectors

$\ket{\psi}$ ("ket $\psi$") in a *Hilbert space*.

2. A physically measurable property $\lambda$ of a quantum system represented by

a linear operator $L$, which has a complete set of states

$\left\{ \lambda_i \right\}$ which form a complete, orthonormal basis in the

Hilbert space

$$L \ket{\lambda_i} = \lambda_i \, \ket{\lambda_i} \,,$$

$$\mathbb{1} = \sum_i \ket{\lambda_i} \bra{\lambda_i} \,.$$

The possible values $\left\{\lambda\right\}$ are identified with real

eigenvalues $\left\{\lambda_i\right\}$ of $L$. A measurement of the property

$\lambda$ which yields the value $\lambda_i$ leaves the system in the state

$\ket{\lambda_i}$.

3. If $\ket{\psi}$ is expanded in terms of the eigenstates of the observable

$$\ket{\psi} = \sum_j c_j \, \ket{\lambda_j} \,, \ c_j = \innerprod{\lambda_j}{\psi} \,.$$

`... (some other stuff I didn't catch---I'll need to look at the proper

lecture notes.)`

4. Suppose there are two properties, $\lambda$ and $\mu$, which correspond to

the operators $L$ and $M$. If $\comm{L}{M} = L \, M - M \, L = 0$, then it

is possible to form states which are pure with respect to both $\lambda$ and

$\mu$, which implies that we can find simultaneous $\lambda$ and $\mu$.

$$\begin{cases}

L \ket{\lambda_i, \mu_i} = \lambda_i \, \ket{\lambda_i, \mu_i} \,, \\

M \ket{\lambda_i, \mu_i} = \mu_i \, \ket{\lambda_i, \mu_i} \,.

\end{cases}$$

TeX

Writing in TeX was relatively drama-free, since I didn’t load too many packages. It’s doable, but it was also pretty annoying. I did fine, and got the notes finished in about ten minutes or so, which isn’t too bad considering how little I use pure TeX anymore.

One of the things that makes TeX quite easy to use is its document class system,

which are essentially templates with a bunch of pre-defined macros. Just anout

everyone uses the article class, and maybe the memoir class if they’re

typing something longer, but most people don’t venture out any further than

that. The article class tends to be relatively sane, and it doesn’t do

anything that I wouldn’t want it to do. The margins are a bit wide, but I can

fix that pretty easily.

Overall, writing a small TeX file like this was pretty easy, but writing something longer, or getting more into the weeds, is a fucking nightmare. Also, remembering the packages you need to use is a pain in the ass.

The TeX file I used to compile the notes and its output.

\documentclass[fleqn]{article}

\usepackage{amsmath}

\usepackage{amssymb}

\usepackage{amsthm}

\usepackage{fontspec}

\usepackage{unicode-math}

\usepackage[default]{fontsetup} % use NewComputerModern, since it's pretty nice

\usepackage{soul}

\usepackage{microtype}

\usepackage{datetime2}

\title{The postulates of quantum mechanics}

\author{Plasmon}

\date{2025-10-21}

\newcommand{\ket}[1]{\left| #1 \right>}

\newcommand{\bra}[1]{\left< #1 \right|}

\newcommand{\expval}[2]{\left< #1 \! \mid \! #2 \right>}

\newcommand{\comm}[2]{{\left[ #1 , #2 \right]}}

\begin{document}

\maketitle

\begin{enumerate}

\item The possible states of a quantum system are represented by normalized

vectors $\ket{\psi}$ (``ket $\psi$'') in a \emph{Hilbert space}.

\item A physicall measurable property $\lambda$ of a quantum system

represented by a linear operator $L$, which has a complete set of states

$\left\{\lambda_i\right\}$ which form a complete, orthonormal basis in

the Hilbert space,

$$L \ket{\lambda_i} = \lambda_i \ket{\lambda_i} \,,$$

$$\mathbb{1} = \sum_i \ket{\lambda_i} \bra{\lambda_i} \,.$$

The possible values $\{\lambda\}$ are identified with real eigenvalues

of $L$. A measurement of the property $\lambda$ which yields the value

$\lambda_i$ leaves the system in the state $\ket{\lambda_i}$.

\item If $\ket{\psi}$ is expanded in terms of the eigenstates of the

observable,

$$\ket{\psi} = \sum_i c_i \ket{\lambda_i}\,, \ c_i = \expval{\lambda_i}{\psi} \,.$$

{\ttfamily ... (some other stuff I didn't catch---I'll need to look at the

proper lecture notes.)}

\item Suppose there are two properties, $\lambda$ and $\mu$, which

correspond to the operators $L$ and $M$. If

$\comm{L}{M} = L \, M - M \, L = 0$, then it is possible to form states

which are pure with respect to both $\lambda$ and $\mu$, which implies

that we can find simulataneous $\lambda$ and $\mu$,

$$\begin{cases}

L \ket{\lambda_i, \mu_i} = \lambda_i \ket{\lambda_i, \mu_i} \,, \\

M \ket{\lambda_i, \mu_i} = \mu_i \ket{\lambda_i, \mu_i} \,.

\end{cases}$$

\end{enumerate}

\end{document}

Typst

I don’t want my commentary to be too colorful here, but I found working with

Typst to be a bit frustrating, likely because I didn’t have a whole lot of

experience using it (crazy, I know). Configuration was easy enough—there’s

certainly a method to Typst’s madness—but there were some quirks that take

getting used to. I didn’t feel like writing a whole bunch of code to make a

title that I liked, so I just stuck with the default title behavior (e.g. no

authors or dates). The rule system, while I think it’s a little ugly—and

there’s probably a better way to do it than just writing a bunch of #set and

#show rules on separate lines—does work very well.

Above all, Typst is consistent, and I really appreciate that. There are certain

elements of the math syntax that irk me though. Since I’ve been a TeX user for

a while, I’m used to writing fractions as \frac{numerator}{denominator}; other

macros which have multiple inputs, like \comm{A}{B} function in the same way.

This means that writing something like \ket{\lambda_i, \mu_i} just works how

you would expect out of the box. Since Typst uses functions, however, you need

to modify your output a bit—you need to use an escape character comma in order

to write ket(lambda_i\, mu_i) to get $\left| \lambda_i, \mu_i \right>$

out—and if you don’t, Typst will complain that there’s an unexpected argument

in the function. This is fine, but it takes getting used to.

The other major thing that bothered me was the fact that spacing math was

annoying as hell. I’m not trying to be dramatic here, but Typst puts a

huge amount of space around certain elements, such as the pipe symbol (|),

because it’s used often in defining sets and whatnot. I know that I’ll need

to use the h function to get rid of the spacing there. The other major thing,

the space.hair symbol, was a pain in the ass to write—there needs to be an

easier symbol to use to actually write stuff.

Even factoring in the fact that I’m not very experienced with Typst, the mathematical typesetting experience was, in my opinion, much worse than TeX’s.

Despite that, the compile speeds were incredibly impressive. It was really easy

to pop in a typst watch 02_typst.typ, open up the PDF, and then see it get

compiled every time I wrote changes to the typst file. Compiling the file took

somewhere around 100–600 milliseconds, whereas XeLaTeX consistently takes

around 2.4 seconds. Likewise, Typst’s compiler gave much more useful error

messages than TeX, and it didn’t complain about any overfull h-boxes. From a

user’s perspective, this is great.

The Typst file I used and its output.

#set text(

font: "New Computer Modern"

)

#show math.equation: set text(font: "New Computer Modern Math")

#show title: set align(center)

#show title: set text(size: 20pt)

#show title: set block(below: 1.2em)

#show title: set text(weight: "regular")

#show title: set rect(

width: 75%,

)

#set par(

first-line-indent: 1.5em,

justify: true,

spacing: 0.65em,

)

// math formatting

#set math.frac(style: "horizontal")

#let frac(a, b) = math.frac(a, b, style: "vertical")

// math "macros"

#let ket(state) = $bar.v #h(0fr) state chevron.r$

#let bra(state) = $chevron.l state #h(0fr) bar.v$

#let innerprod(thing1, thing2) = $chevron.l thing1 #h(0fr) | #h(0fr) thing2 chevron.r $

#let comm(thing1, thing2) = $[ thing1, thing2 ]$

#set document(

title: [The postulates of quantum mechanics]

)

#title()

+ The possible states of a quantum system are represented by normalized vector

$ket(psi)$ ("ket $psi$") in a _Hilbert space_.

+ A physical, measurable property $lambda$ of a quantum system is represented by

a linear operator $L$, which has a complete set of states ${lambda_i}$ which

form a complete, orthonormal basis in the Hilbert space,

$ L ket(lambda_i) = lambda_i ket(lambda_i) space.hair ,$

$ bb(1) = sum_i ket(lambda_i) bra(lambda_i) space.hair . $

The possible values ${lambda}$ are identified with real eigenvalues of $L$. A

measurement of the property $lambda$ which yields the value $lambda_i$ leaves

the system in the state $ket(lambda_i)$.

+ If $ket(psi)$ is expanded in terms of the eigenstates of the observable,

$ ket(psi) = sum_i c_i ket(lambda_i) space.hair , space c_i = innerprod(lambda_i, psi) space.hair . $

`... (some other stuff I didn't catch---I'll need to look at the proper

lecture notes.)`

+ Suppose there are two properties, $lambda$ and $mu$, which correspond to the

operators $L$ and $M$. If $comm(L, M) = L space.hair M - M space.hair L = 0$, then it

is possible to form states which are pure with respect to both $lambda$ and

$mu$, which implies that we can find simultaneous $lambda$ and $mu$,

$ cases(

L ket(lambda_i \, mu_i) &= lambda_i ket(lambda_i \, mu_i),

M ket(lambda_i \, mu_i) &= mu_i ket(lambda_i \, mu_i)

)

$

Conclusion

Typst was pretty alright to use, and I’m going to be using it more (albeit more privately) to do some typesetting. I’m not sure if I’ll fully switch to it yet, but I think that it warrants more investigation. I’ll need to compare TeX and Typst with a more substantial project than compiling more than around 3/4 of a page worth of notes, and I’ll need to familiarize myself with Typst more. I think it would be worth trying to write a Typst template from scratch—no external packages allowed. This would be a really painful process, but it would be interesting to see what I could do.

Sorry if this followup was insubstantial compared to the behemoth from a few days ago.

#Software #Typography #Typst Series